It is the engaged feminist intellect (like John Stuart Mill’s) that can pierce through the cultural-ideological limitations of the time and its specific “professionalism” to reveal biases and inadequacies not merely in the dealing with the question of women, but in the very way of formulating the crucial questions of the discipline as a whole.

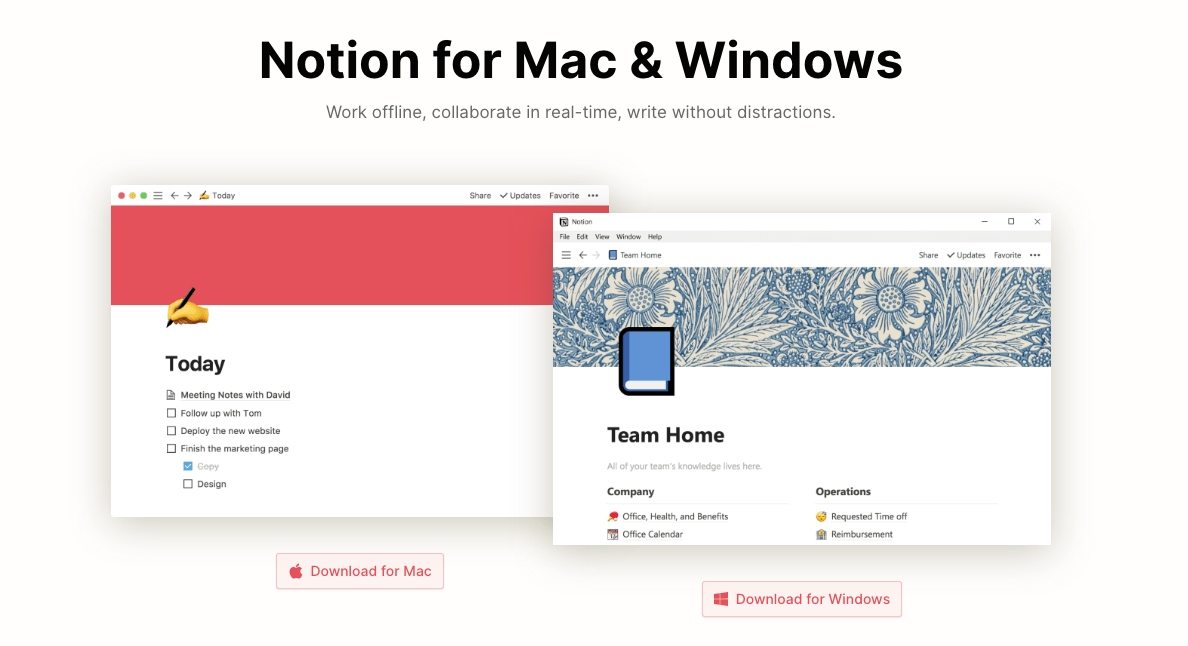

NOTION APP MUSIC NOTATION SERIES

Just as Mill saw male domination as one of a long series of social injustices that had to be overcome if a truly just social order were to be created, so we may see the unstated domination of white male subjectivity as one in a series of intellectual distortions which must be corrected in order to achieve a more adequate and accurate view of historical situations. At a moment when all disciplines are becoming more self-conscious, more aware of the nature of their presuppositions as exhibited in the very languages and structures of the various fields of scholarship, such uncritical acceptance of “what is” as “natural” may be intellectually fatal. In revealing the failure of much academic art history, and a great deal of history in general, to take account of the unacknowledged value system, the very presence of an intruding subject in historical investigation, the feminist critique at the same time lays bare its conceptual smugness, its meta-historical naïveté. In the field of art history, the white Western male viewpoint, unconsciously accepted as the viewpoint of the art historian, may-and does-prove to be inadequate not merely on moral and ethical grounds, or because it is elitist, but on purely intellectual ones. And it is here that the very position of woman as an acknowledged outsider, the maverick “she” instead of the presumably neutral “one”-in reality the white-male-position-accepted-as-natural, or the hidden “he” as the subject of all scholarly predicates-is a decided advantage, rather than merely a hindrance of a subjective distortion. In the former, too, “natural” assumptions must be questioned and the mythic basis of much so-called “fact” brought to light. If, as John Stuart Mill suggested, we tend to accept whatever is as natural, this is just as true in the realm of academic investigation as it is in our social arrangements. 1 Like any revolution, however, the feminist one ultimately must come to grips with the intellectual and ideological basis of the various intellectual or scholarly disciplines-history, philosophy, sociology, psychology, etc.-in the same way that it questions the ideologies of present social institutions.

While the recent upsurge of feminist activity in this country has indeed been a liberating one, its force has been chiefly emotional-personal, psychological and subjective-centered, like the other radical movements to which it is related, on the present and its immediate needs, rather than on historical analysis of the basic intellectual issues which the feminist attack on the status quo automatically raises. A version of this story originally appeared in the January 1971 issue of ARTnews.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)